Write a Script

Digital storytelling allows computer users to become creative storytellers by first beginning with the traditional processes of selecting a topic, conducting research, writing a script, and developing an interesting story. This material is then combined with various types of multimedia, including still images, recorded audio, computer-generated text, video clips, and music so that it can be played on a computer, added to a web site, posted on a blog, or burned on a DVD.

The script for an educational digital story is one of the most important components that students will create. We stress to our students and workshop participants that a good digital story must first be a good story and that no matter how much expertise a student has with technology, a poorly written story will not be improved by fancy transitions and other digital effects.

Scriptwriting can be difficult for many students and is certainly more work and less fun than some of the other tasks associated with creating a digital story, like searching for images or adding music. However, digital storytellers at all levels should understand that a well thought out, well written script is an absolute requirement for a good digital story and we require our students to begin writing the script for their story before they begin work on creating the digital story. The script should stand on its own merits, even if there are no visuals, narration, music, animations, or other components that will eventually add interest to the digital version.

The First Version of the Script

Students in our courses and workshops are asked to write and submit a first draft version of the script for a digital story based on their selected topic. They are usually allowed to choose their own topics, although they are encouraged to select a topic related to historical events, personal episodes in their lives, or instructional content that describes an educational theme or concept.

Students view example stories that usually include a personal element in the script so that the digital story reflects ideas that the digital story creator feels passionate about. Even with personal stories, we encourage students to try to integrate instructional elements tied to content so that the final version of the story has at least some connection to education.

Concentrating their efforts on writing a script shifts the emphasis away from finding images to illustrate a story, which many younger students want to begin with, and allows them to spend more time on the “storytelling” instead of the “digital.” and provides students with an opportunity to take ownership of the story through the personal nature of their writing. Daniel Meadows, a leading proponent of Digital Storytelling in the UK, notes that almost half the time in a five day workshop is spent working on scripts. And his belief that time spent writing and revising a script is time well spent, has proved to be true for our students as well. More information is online at: http://franklinds.wikispaces.com/file/view/dst_script_writing.pdf

Tom Banaszewski conducted a Master’s Thesis in which he investigated the use of Digital Storytelling in Grades 4 through 12, by examining the storytelling process, the motivation of teachers and the possible alignment of Digital Storytelling with curricular goals and school district or statewide education standards. In his study, Banaszewski echoes the opinions of many that when the focus is just on the technology of creating digital stories and other literacy skills are ignored, a number of troubling issues arise:

- Students cannot explain what Digital Storytelling is and why it is different from a computerized slideshow;

- Students do not recognize the power of their own voices;

- Students concentrate on using the computer before a story’s script has been completed; and

- Students waste time on unnecessary transitions and special effects.

Banaszewski proposes that the solution to these issues is for students (and teachers) to concentrate on developing narrative skills and focusing on what makes a good non-digital story, the same established practices found in traditional writing and composition classes. In his own classroom, he notes that the technology was always secondary to the storytelling, a view that cannot be overemphasized.

Story Circles

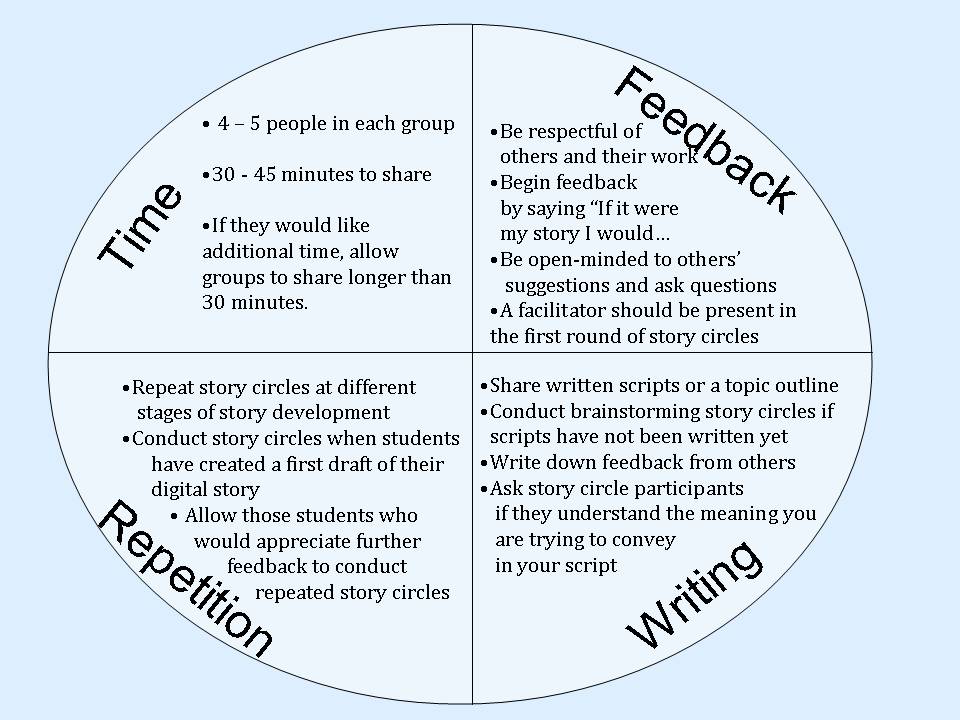

After the initial versions of the scripts are written, students should participate in small group “story circles” in which they share their ideas for their stories, read draft versions of their scripts and provide constructive criticism and suggestions that can be used to improve the scripts and the overall plan for the final stories. Describing the importance of story circles, The Center for Digital Storytelling’s Joe Lambert writes: “students that share their stories in our circles recognize a metamorphosis of sorts, a changing, that makes them feel different about their lives, their identities.”

Lambert uses writing prompts to get the script writing process started. Here is a popular prompt he uses:

In our lives, there are moments, decisive moments, when the direction of our lives

was pointed in a given direction, and because of the events of this moment, we are

going in another direction. Poet Robert Frost shared this concept simply as The Road

Not Taken. The date of a major achievement, the time there was a particularly bad

setback, meeting a special person, the birth of a child, the end of a relationship, the

death of a loved one are all examples of these fork-in-the-road experiences. Right

now, at this second, write about a decisive moment in your life.

Additional prompts that could be used include some from the CDS, from Bernajean Porter, and others:

- Tell the story of a mentor or hero in your life.

- Tell the story of a time when things in your life were not going so well and you felt really scared.

- Tell the story of a time in your life when things worked out much differently than you expected.

- Tell the story of a "first": first love, first day on a job, first time trying something really difficult, the first time you read a favorite book, heard a favorite song, saw a favorite movie, etc.

- Describe a moment in time when you knew you would never be the same again.

Mechelle De Craene provides a helpful strategy for improving what she calls “literature circles,” especially when students are learning to create digital stories. De Crane suggests assigning specific roles to members of a group to help keep students just beginning to use Digital Storytelling on task. Some of the roles she recommends include the following:

- Discussion Director – leads the group discussion

- Summariser – provides a synopsis of the main ideas and character generation

- Investigator – researches the topic for useful background information

- Illustrator – creates visual sketches, concept maps, flow charts, etc.

Story Circle Etiquette

When giving feedback:

- Be respectful of others and their work.

- Begin your feedback by saying something like: "If it were my story, I might..."

- If you have questions about anything in the script, ask about it in a constructive way.

When receiving feedback:

- Be receptive to suggestions of others.

- Ask questions about any portion of the feedback that needs further clarification.

- Remember that the main benefit of story circles is that someone who is not as familiar with your topic as you are, can provide an objective opinion of your work and make suggestions for how you can revise your script to make it clearer and more appealing to potential viewers.

The Writing Challenge

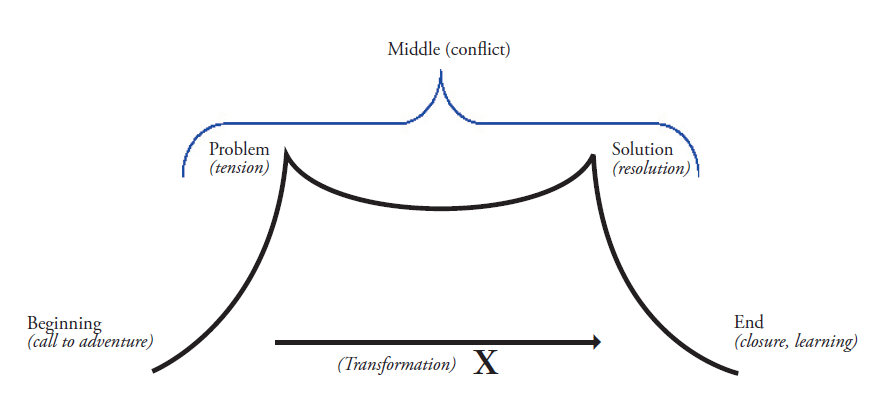

Many students have trouble learning to formulate an educationally sound argument, and just providing students with a library of digital images and computer-based authoring software will not be beneficial to students or educators. There are many helpful resources for students, and Ohler and Dillingham’s Visual Portrait of a Story as shown in the figure below is part of a detailed description of story elements that can be helpful to students and educators as they construct their own stories.

This graphic is online at: http://www.jasonohler.com/pdfs/VPS.pdf

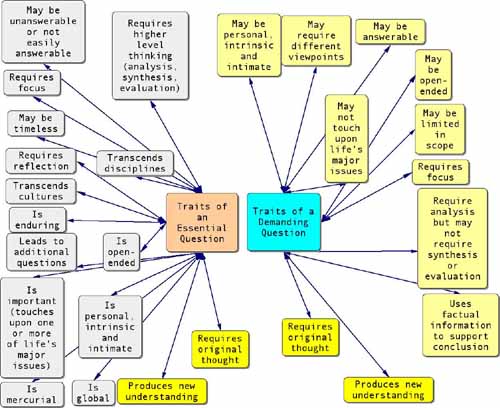

A Questioning Toolkit has been online for many years and is still a great resource. This website can be used to introduce students to effective questioning techniques that may help them in their attempts to formulate the dramatic questions that will form the basis of their own stories.

Another older, but still very helpful resource is The (merely) Demanding Question webpage, written by Jamie McKenzie in 2006. It contains lots of useful information about the essential questions and how they can be used by educators and students.

More information about script writing may be found online at the following websites:

-

Digital Storytelling and the Writing Process

https://www.writecenter.org/blog/digital-storytelling-and-the-writing-process

-

Digital Storytelling: Extending the Potential for Struggling Writers

http://www.readingrockets.org/article/40054

-

Create Script (from Helen Barrett's Site on Digital Storytelling in ePortfolios)

https://sites.google.com/site/digitalstorysite/process/create-script

-

Getting the Story Down On Paper (beginning on page 11 in A Guide to Digital Storytelling)

http://www.bbc.co.uk/wales/audiovideo/sites/yourvideo/pdf/aguidetodigitalstorytelling-bbc.pdf